Embedding multiple x86 programs inside a single binary

Binary overlapping

Computer programs comes in all shapes and sizes, but one of the most important form is x86 binary executables. These files can be read by an x86 CPU and will alter the CPU state in some way. Much effort has gone into how we represent these binaries, like making them smaller so that they execute faster. But also much effort has gone into making them harder the read when decompiled, aka being turned back from binary into human-readable text. People do this to for instance protect intellectual property, but also to hide malicious code. It is vital for us thus to understand all forms of which is possible to get both the optimization and to defend ourselves against malicious actors.

One still completely undiscovered is that of binary overlapping. Where the same byte sequence can be interpreted as multiple programs if you start parsing with just one byte off. The key distinction that we do not start parsing at the start of a different instruction, but always somewhere in the middle, and keeping it that way for as long as possible.

When an x86 CPU executes a program, a pointer points towards a sequence of bytes. The CPU will read these a byte at a time until the CPU recognizes the instruction and it will execute it. After execution is done, it will continue reading bytes until it recognizes an instruction repeating this process. The CPU’s today will not strictly adhere to this model anymore and it might execute/parse instructions in advance under the hood already, but it still has to guarantee this model works. We will also consider this model because other software like disassemblers typically works this way.

In x86, instructions are by definition anywhere between 1-15 bytes long, they follow a complex encoding scheme which we will ignore for now. Furthermore, the word “instruction” is a little bit ambiguous, since it can refer to

- the mnemonic, i.e ADD

- the assembler form: i.e ADD rax, 2

- the binary encoding, i.e for ADD that might be 0x10 0x34.

And a program is a simple list of instructions.

So let us dive into the good stuff!

Consider the binary following binary sequence. The lines are separated on an instruction level basis. The values in hexadecimal are displayed to the left, and the corresponding assembler form to the right.

0f 0d c0 NOP EAX, EAX

90 NOP

90 NOP

31 ff XOR EDI, EDI

If executed by the CPU, it will first read the byte 0f, this doesn’t mean anything yet. So we will parse a second byte, c0. Still nothing, then we read d0 and we get a specified instruction. In this case NOP EAX, EAX. Best described as “No OPeration executed with register EAX and EAX”.

Afterward, we read two NOPs and a XOR instruction that XORs both its inputs. Hence zeroing out all content.

What this program does is not that interesting. After all, it does nothing for a bit and then only zero’s out an register. But after 3 years this is the most beautiful program I could think of.

First things first, why do we execute the same operation for the byte sequence 0f 0d c0 as for 90. How is it possible that two byte-sequences that share not a single byte represent the same instruction?

If we look up 0f 0d c0 in the x86 instruction set manual, we can see that it is an instruction for prefetching hints. So it should not affect the state on the CPU (or at least observable to us). Hence the disassembler in which I generated this output decided it was equivalent to a NOP and should be displayed as such.

However, this above piece of code is only disassembled like that because I threw it inside a proper disassembler (intel’s XED in this case). Let’s take a look at the output of an arguably more well-known disassembler, objdump.

0f prefetch (bad)

0d c0 90 90 31 or $0x319090c0,%eax

....

Three interesting things happened here, first of all, it didn’t decode it correctly. Which isn’t too uncommon even in mainstream disassemblers if you start hunting for it[0]. The second interesting thing that happened is that we suddenly obtained a totally new instruction that we have not seen before by starting execution/parsing one byte later, while still using the same original byte sequence!

But most importantly of all, what is the next executed instruction? We know it is should be the next byte in the stream, so looking at the first output: here we can see it should start with FF.

If we would continue this, we would have to completely independent programs inside the same original binary sequence!

Use-cases

This technique has 2 very interesting use-cases. The original use-case, and the reason why I came up with this idea, is obfuscation. Notice that in the second output, the output of the disassembler objdump, can now theoretically be completely different program from what another actor, like your CPU, could read. Implying that malware can be completely hidden from malware analysis or automatic analysis tools without any overhead. Only by exploiting a single parsing error. Which can be guaranteed against most common disassembler parsing techniques (this will the topic of another blog).

The second and probably more exciting use case is performance. In the examples above we didn’t give that much thought on what the programs are or are supposed to look like.

But let us consider a program P. If we take the second half of P, and we were magically able to alter the first half of P such that its functionality would be retained, and that if you would start parsing from the second byte it would execute the second half of the original P. Then we have effectively halved our program size! And we could continue doing this until we have reduced it by a massive factor.

Required properties for overlapping

If we consider binary sequence, we say they are binary overlapping, if and only if, we can obtain a program P1 and P2 such that

- To execute P1, we start executing at a different byte in the byte sequence than for P2

- For each instruction in P1, no instruction ends with the same byte index in the sequence as any other in P2

The first property is to ensure we talk about programs that are obtained by starting at a different location than another.

The second property is there to stop them from converging. If this property wasn’t satisfied, any 2 different programs would converge into the same from that point onwards, example:

ff c5 inc ebp

fc cld

77 90 ja 0xffffffffffffff95

90 nop <- same as the second stream

...

...

c5 fc 77 vzeroall

90 nop

90 nop <- same as the first stream

...

...

Obtaining these binaries

We have 3 options that I’m aware of for obtaining these binaries. We can write these binaries by hand, this is, of course, no option besides for very specialized cases and probably not worth it.

The second option is by trying to alter the generation process of our compiler/assembler. Computationally generating binaries like this is heavy and our current tooling is not designed to support generating these binaries.

Compiler Generation

Let me illustrate the complexity with the following example:

Suppose we have 2 programs P1 and P2, which we want to overlap. Meaning that the first byte of P2 should be the second byte of P1.

Consider that P1 is a simple program that wants to first execute an add followed by a mov, while P2 wants to execute an xor followed by a jmp. For brevities sake, I omitted possible arguments.

Our magical super awesome assembler would look at P1, recognizes that we should output a binary encoding for add. Now it would look up which bytes are defined to represent add and it would emit it to some structure.

Let’s say for add the assembler emitted 10 AE.

Now before we continue, we have to satisfy that P2 also gets generated correctly. Unfortunately for us, the xor instruction is defined to be 06 84.

In its current form, it seems as if add and xor are incompatible for binary overlapping.

Luckily for us, due to the incredibly complex nature, there is a large set of transformations that can help to remedy this situation.

For instance, it is not completely uncommon that an instruction has a different encoding. So while add was first defined to be 10 AE at first, it might be the case that in the documentation an equivalent encoding exists for our use-case, so maybe we might substitute it with 30 06 84 20. Enabling us to binary overlap at a cost of lengthening P compared to what we otherwise would.

So now we got add and xor to overlap. But now we run into the same problem for the second instruction for P1, our generated encoding for mov may now only start with 20!

This means that chance of being able to satisfy the overlapping properties for instructions is incredibly small. Hence we need every help we can get through combining many different techniques, such that we get an acceptable rate of being able to produce our desired binaries.

Overview of generation techniques

Through the 3 years that I have been thinking about this problem, I accumulated a list of possible techniques:

- use a semantically equivalent instruction, like changing

ADD 1toINCremenent. Usingprefetchwdirectives instead ofNOPs. - change an instruction encoding by using different prefixes or encoding mechanisms. If an instruction ends with

48, we can simply prepend48to any instruction and it will be considered as a prefix. Guaranteeing overlap. - re-order instructions before they get used like done in out-of-order execution

- alter an instruction, but appending the inverse of the change. i.e

ADD 2would becomeADD 5withSUB 3appended. This technique can also be used with memory locations but requires much more setup - jumping ahead a few bytes S.T we can use later bytes instead of the current one in a given stream

- inserting nop’s or equivalents (or something like

addandsubwith the same argument). NOP’s are great since these can have long arbitrary arguments see [1] - let instructions use different registers

- let instructions switch between using registers or memory

All of these techniques require extensive knowledge of the program and/or instruction set to a level typically not available to an assembler. Luckily if implemented gives an enormous search space in which we can find potential candidate programs since we can keep infinitely combining them. In a future blog, I will expand these entries.

STOKE

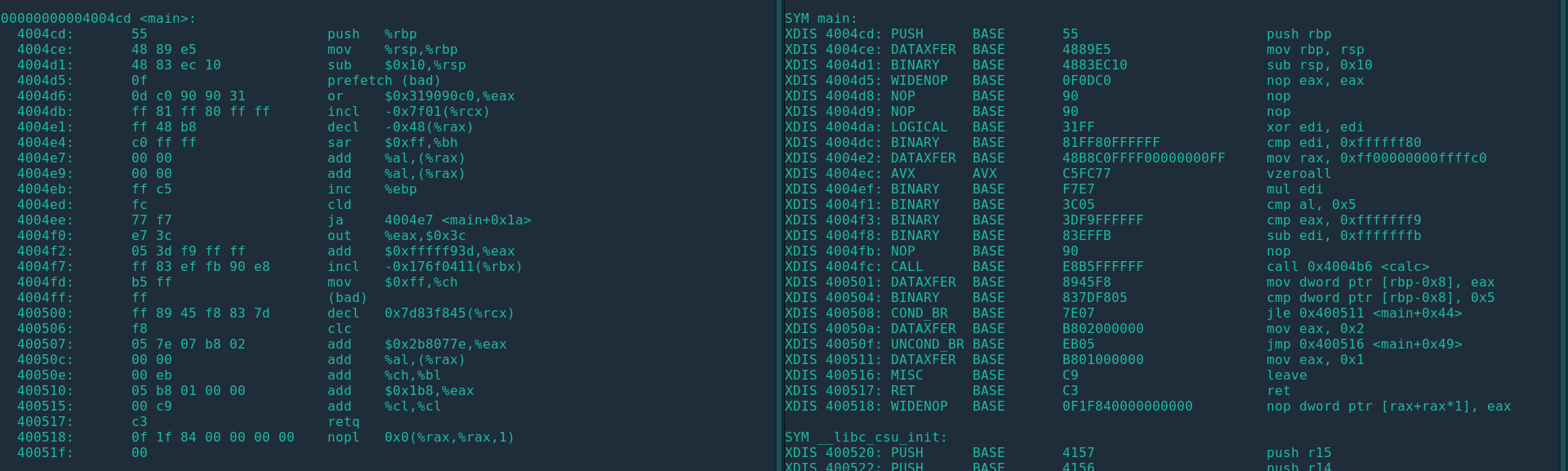

While compilers are mostly deterministic (or based on deterministic processes), we also have so-called super optimizers. These typically alter a given program with some sort of randomness attached. While Implementing techniques so that arbitrary programs can be generated still requires a large engineering effort. However, I temporarily circumvented this problem by modifying STOKE[2] with a custom cost function for generating the largest program that still is overlapping. The result is a 70+ byte binary, albeit it did not preserve my original given semantics, it did prove the existence of these objects. Enough in my opinion to warrant further research into this direction. Below is a picture of the found binary, I also gave it the requirement of starting with an instruction that objdump wouldn’t recognize. Meaning that it also demonstrates a method on how to hide programs from disassemblers. You can see a full-screen version of the image here

The next step

The next step that should be taken is implementing more techniques like described above. Currently, experiments on STOKE are run with the limitation that STOKE mainly performs contextless mutations randomly to a binary. Heavily limiting the effectiveness. Verifying more context-dependent mutations was always a major issue.

However, with new recent work, nearly the entire semantics of x86 instruction set have been formally encoded[2] and implemented in STOKE. With this, we can start moving from arbitrary mutations to new novel optimizations.

This is a topic I will be researching for the coming year. If you are interested here is my follow up blog on how we can model this problem a lot easier!

[0] Paleari, R., Martignoni, L., Fresi Roglia, G., & Bruschi, D. (2010, July). N-version disassembly: differential testing of x86 disassemblers. In Proceedings of the 19th international symposium on Software testing and analysis (pp. 265-274).

[1] Jämthagen, Christopher, Patrik Lantz, and Martin Hell. “A new instruction overlapping technique for anti-disassembly and obfuscation of x86 binaries.” 2013 Workshop on Anti-malware Testing Research. IEEE, 2013.

[2] Dasgupta, S., Park, D., Kasampalis, T., Adve, V. S., & Roşu, G. (2019, June). A complete formal semantics of x86-64 user-level instruction set architecture. In Proceedings of the 40th ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation (pp. 1133-1148).